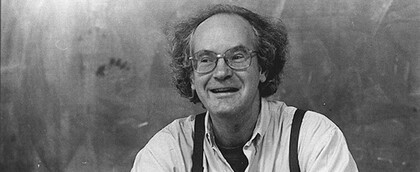

Liquid Architecture is honoured to present Michel Chion’s work in Australia for the first time.

Michel Chion is arguably the world’s foremost thinker on sound and the cinema. Since the 1980s, he has written extensively on the relationship of sound and image, publishing in 1990 what has become the foundational guide to the subject, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. In this momentous book, Chion advances a whole new lexicon for describing audio-visual concepts, via the works of Jacques Tati, Alfred Hitchcock, Jean-Luc Godard and others. Audio-Vision cemented Chion’s place in a legacy of writing on film-sound across the history of cinema, following classic examples like Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov’s 1928 ‘Statement on Sound’, which theorised the end of the ‘silent’ era, and Bresson’s ‘Notes on Sound’, an auteurist poetics penned in 1975. In Chion’s writing, theoretical and poetic modalities overlap. Indeed, on reading Audio-Vision, film scholar Claudia Gorbman was moved to name Chion ‘a poet in theoretician’s clothing.’

Michel Chion’s exceptional sensitivity to film sound reflects and expresses his long-standing practice as an avant-garde composer. In the 1970s he was a member of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM), the influential collective led by composer and theoretician Pierre Schaeffer dedicated to furthering the art of musique concrète through experiments in audiovisual communication, audible phenomena and music in general. It was at the GRM that Chion composed arguably his most famous work, Requiem, a noisy and surreal deconstruction of the Funeral Mass made whilst pondering the ‘troubled minority of the living, rather than the silent majority of the dead.’

More than a composer and canonical theorist, Chion the practitioner is one of the few remaining champions of Schaefferian ‘reduced listening’. Reduced listening is an analytic method in which recorded sounds are played on repeat over long durations in order to reveal hidden details and dimensions of the ‘sound itself’. Chion’s continued insistence on the importance and integrity of this practice, and the attendant assertion of a ‘sonic object’, is at the centre of one of musique concrète’s most important debates: whether sounds can, or indeed should, ever be fully excised from their meanings and associations. In many ways, however, the question of one or the other is misleading. For Chion, reduced listening is rigorous but not exclusive; there is always both the ‘sonic object,’ and the listening encounter. In his conception, reduced listening does not foreclose other modes of listening—semantic, causal, political, social—but rather seeks deliberately to expand discourse, opening sonic experience to further revelation, through both the act of listening, and sustained attention how we listen—listening to listening.

Sometimes, Chion describes himself as more a scientist than a philosopher, giving the example of early nineteenth-century British meteorologists first studying clouds. For a long time, clouds were just clouds. But as skilled and patient observers began to notice patterns in shape and form, the idea of noting and naming recurring formations led to the first in-depth investigations, classifications and publications on clouds and their causes, and weather became a discipline. From reduced formal analysis, other ways of knowing can take shape, ‘things’ that were indistinct may become particular. Chion thinks of sounds as cloud-like forms that shape-shift in air, perceivable only in flux, but suggestively full of understandings yet to emerge.

Artists